Continuing our Flower Power Series: Water Lily

Water lilies are one of the prized jewels; shimmering beauties floating in the aquatic world. They belong to a family of flowering plants called Nymphaeaceae where water lilies comprise over 30 of the 70 species. Water lilies live as rhizomatous aquatic herbs in both temperate and tropical climates throughout the world.

Rhizomes are plant stems which are modified from the upright, above-ground plants we usually see. Upright plants have a stem which supports the plant and sends out new shoots from the roots. Rhizomes are actually a type of stem, but they have nodes which grow “horizontal roots” through asexual reproduction (vegetative propagation) from the upper portion of the node (think of potatoes or ginger root).

Rhizomes vary greatly from plant to plant, but they all have a similar structure which provides a protective mechanism and helps perennial plants survive in difficult environments. The water lily “root” system anchors within the soil of the pond or pool of water with long stems connecting the roots to the leaves and flowers floating on the surface.

The name of the family, Nymphaeaceae, has Greek/Latin origins inspired by mythology. In ancient mythology nymphs were minor female nature deities or supernatural beings and, in this case, associated with water. These nymphs later came to be known as water fairies or water sprites.

The flowers of water lilies have many petals, at least 8 and usually many more than that. The colors range from white, through pink, reds, blues to pale yellow. Their centers are most often crowded with yellow stamens.

The leaves of water lilies are roughly circular with a handy slit in one side (where the base of the leaf stalk attaches) where rain water can drain off, enabling them to stay afloat.

Some varieties of water lily achieve a total width of 12 feet, but most are about half that. The smallest documented species of water lily was thought to have gone extinct in its native Rwanda but fortunately was saved by a horticulturist from Spain. The leaves measure only 1 cm. across and the tiny flowers are white with yellow stamens, rising a few centimeters above the plant.

By contrast, the world’s largest water lily is called Victoria amazonica (image above). These giants were named in honor of Queen Victoria. The enormous leaves (see top of above image) measure up to 10 feet across and are held up by an underwater stalk up to 26 feet long. The edges of these leaves are turned up, forming a shallow cup and are able to support the weight of a small child.

The underside of each leaf contains a series of sturdy cross-ridges (spines or ribs) which keep them spread out and flat on the water’s surface. Air is trapped in the spaces between the ribs on the underside and assists with buoyancy. The ribs also have an additional advantage of discouraging fish from nibbling on the leaf.

Other special adaptations allow water lilies to thrive in and contribute to aquatic environments. Because their large, round leaves are exposed on the water’s surface there is maximizal absorption of sunlight for photosynthesis. The lilies contribute to the health of their aquatic ecosystems by providing other organisms shade from the hot sun and also reduces the growth of algae. Water lilies’ leaves and stems provide habitat for frogs, insects, fish (and the odd little duckling) while their flowers provide for pollinators such as butterflies and bees.

Highly adaptable, fast growing and very long lived (from several decades to over a hundred years), water lilies are valued for more than just their beauty.

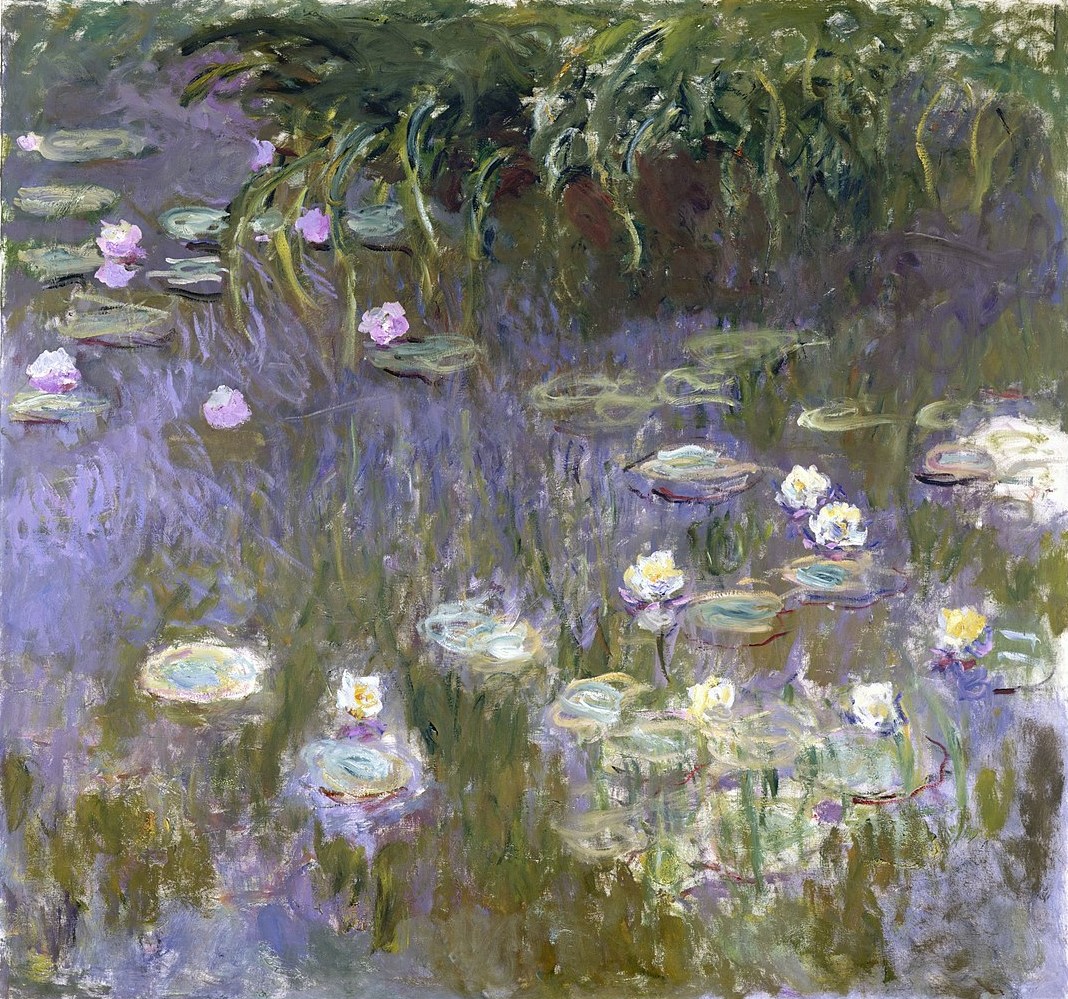

Claude Monet’s (1840 – 1926) long association with water lilies as a subject of his paintings is fascinating. In his life this famous Impressionistic painter came back to water lilies many times, ultimately producing more than 250 paintings, some of them monumental in size. His story is filled with both success and heartbreak as he and his contemporaries eventually broke through the very real barriers of convention in their quest for artistic freedom of expression.

Monet planted the water lilies before he painted them as his commercial success enabled him to hire many gardeners. His garden at Giverny, a village on the right bank of the River Seine and about 80 km west northwest of Paris, was ultimately organized as if it were a huge painting. Monet referred to this garden as “My finest masterpiece”.

Water lilies became a kind of obsession for Monet and interestingly his most challenging subject. He concentrated on painting the surface of the water which reflected the sky. But he needed something to provide a point of reference between water and sky and found it in the presence of the lilies. In other words, he saw his water lilies as a natural bridge between water and sky.

Unfortunately, Monet developed cataracts in later life. This was a mixed blessing as he struggled with anxiety over his impaired sight through several eye operations – and yet his inability to see also produced some of his most evocative works. Due to his failing sight, the colors he used intensified dramatically and this opened the path for abstract painters.

It is believed water lilies are some of the oldest aquatic plants still in existence. Their breathtakingly lovely flowers have, through the ages, captured the hearts of many including gardeners and painters. The art of ancient Greece and Egypt are filled with examples of them.

Some quality in lilies has motivated many cultures to regard them as symbolic of concepts such as purity and devotion. Buddhist meditations have centered on the water lily because of the imagery: the plant’s roots are hidden in the mud under water while a lovely flower rises above the surface. They saw this as outlining the symbolism of striving toward enlightenment.

The ancient Egyptians held the water lily as sacred and saw their complex blossoms as representative of the Upper and Lower parts of the Egyptian empire (another place where they were seen as a connection factor).

The fact that some water lily blossoms open in the morning and close at night made them sacred in ancient Egypt where they were associated with the rising and setting of the sun as well as the cycle of life and death. Egyptian priests and rulers were buried with necklaces of waterlily blossoms as a symbol of resurrection.

We’ll leave you with an insight published by genetic researchers in 2002 showing that water lilies themselves may represent an important connective component in the evolution from plants without flowers to flowering plants.

The difference between flowering and non-flowering plants is found in the structure (tissue) surrounding the seeds (called endosperm). The difference is flowering plants have 3 genetic components in the tissue surrounding the seed while non-flowering plants have only 1 genetic component there. Researchers found that water lilies have 2 genetic components in that same tissue. This led to the hypothesis that the water lily (an extremely ancient plant) was actually an intermediary between non-flowering and flowering plants.

What seems to resurface over and over is the idea of the water lily as a intermediary, connective element or bridge between two things: water and sky, Upper and Lower Egypt, rising and setting of the sun, birth and death, flowering and non-floweirng plants and so on.

Carl Jung said: “Thus a word or an image is symbolic when it implies something more than its obvious and immediate meaning. It has a wider “unconscious” aspect that is never precisely defined or fully explained… As the mind explores the symbols it is led to ideas that lie beyond the grasp of reason.”